Last week, we explored the concept of epigenetics: the cellular software that orchestrates gene activity.

This week, we zoom in further.

[English]

[Korean] 제일 앞 부분 reference에 대한 내용은 NotebookLM이 임의로 잘못 표현한 것입니다. 정확한 각각의 상세 레퍼런스는 아래 본문에 연결되어 있습니다.

Generated by NotebookLM

Aging used to feel inevitable. An irreversible, downhill path.

But that paradigm is breaking.

At the frontier of longevity research, we’re learning that aging isn’t just the result of time. It’s increasingly seen as a loss of epigenetic information — the molecular instructions that tell each cell what to do, what to repair, and how to function.

The DNA remains the same.

But over time, your body forget how to read it properly.

This loss of precision leads to:

• Faulty gene expression

• Weakened repair systems

• Chronic inflammation

• Loss of cellular identity

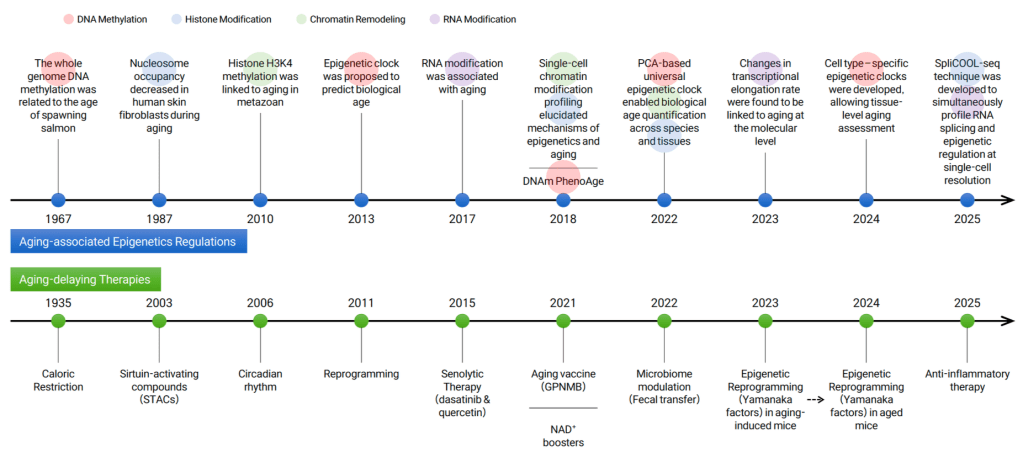

A History of Aging-Related Study

by Junghoon Park, Genolution

The timeline captures two converging threads:

On one hand, we’ve seen decades of progress in lifestyle and pharmacological approaches to slow aging – from caloric restriction in the 1930s to senolytics and microbiome modulation in recent years.

On the other hand, epigenetic research has advanced dramatically, offering new insights into how cells age at the molecular level.

As these two lines of research matured, they began to intersect.

The emergence of tools like epigenetic clocks marked a turning point: a way to quantify biological aging, and assess how well interventions are working.

Let’s explore how that breakthrough came to be.

Epigenetic Clocks: Measuring the Invisible

If you’ve been exploring the world of longevity, chances are you’ve heard of biological clocks.

But how are they actually calculated?

And among the many available clocks, which ones are considered the gold standard?

Let’s break it down.

DNA methylation age of human tissue and cell types,

Steve Horvath, Genome Biology, 2013

Pioneered by Steve Horvath in 2013, epigenetic clocks transformed aging from a vague concept into a quantifiable, trackable process.

Unlike chronological age, your epigenetic age can vary based on lifestyle, disease, or intervention and it often correlates more strongly with mortality risk.

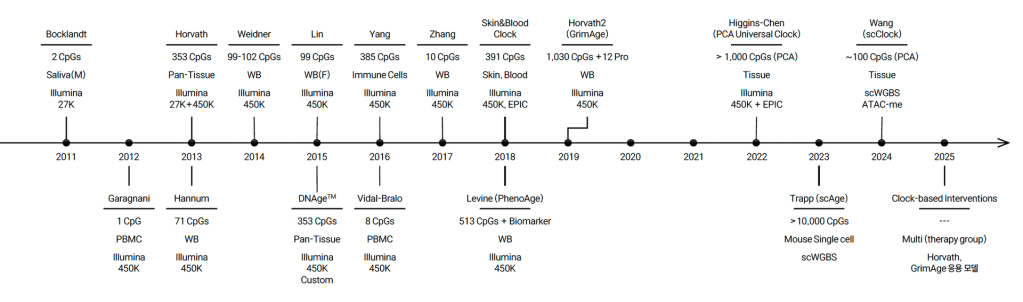

Proliferation of Epigenetic Clocks

by Junghoon Park, Genolution

Thanks to advances in epigenetic profiling technologies, a wide range of epigenetic clocks have been developed over the past decade.

The timeline shows how clock models have evolved. These clocks differ in their accuracy, biological relevance, and practical application.

But together, they reflect a growing effort to capture biological age more precisely and contextually.

It’s an ongoing and rapidly developing area of research with newer clocks integrating more sophisticated biology and higher-resolution datasets.

Why Epigenetic Clocks Matter

They’ve already transformed how we think about aging, from a mysterious decline into something we can track, study, and perhaps one day master.

Their practical use in interventions, and personal diagnostics makes them a vital tool in the longevity toolbox even if they’re not yet the full map.

Here’s how epigenetic clocks are currently being used:

• Measure the impact of anti-aging interventions: Researchers use clocks to test how compounds or protocols affect biological age over time.

• Identify individuals aging faster than average: Epigenetic age can reveal hidden risks that don’t yet show up in medical diagnostics.

• Track rejuvenation in experimental trials: Clocks help detect whether new therapies are truly reversing biological aging.

• Stratify participants in clinical trials: Applying biological age is beginning to be considered for better targeting.

• Monitor personal health journeys: Individuals use clock results to track progress as they adopt lifestyle or supplement routines.

They’ve opened a new chapter in how we evaluate and pursue longevity.

Still, limitations remain.

The Limits of Epigenetic Clocks

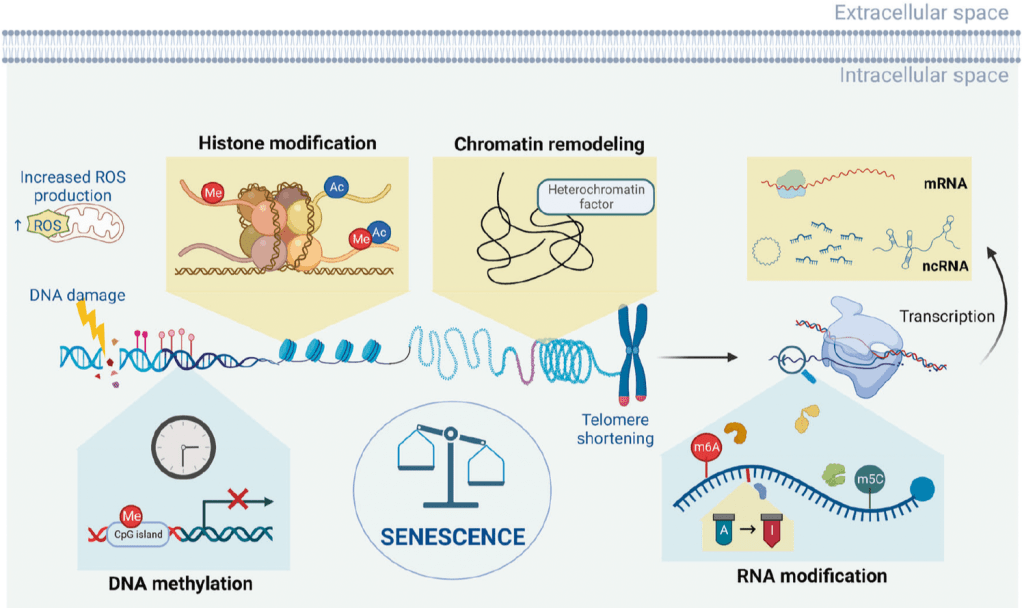

Most clocks focus solely on DNA methylation, which is only one layer of the broader epigenetic landscape. They do not capture histone modifications, RNA editing, or chromatin remodeling — all of which also shift with age and contribute to biological decline.

Moreover, there’s an important scientific debate still unfolding: Do DNA methylation changes cause aging, or are they simply reflections of other underlying damage? Some researchers argue that methylation drift may be more of a downstream symptom than a root cause.

This uncertainty hasn’t diminished their value. But it reminds us that biological age is still a developing field, and no single metric can yet capture the full complexity of cellular aging yet.

Leave a comment