World Health Day was celebrated last week — April 7, 2025

“Let food be thy medicine.” — Hippocrates

The idea that food can heal is gaining popularity in the West recently—but has long been central to Eastern medicine. However, still, what’s healthy for one may not work for another.

A Widely Discussed New Study on Diet and Healthy Aging

A recent Nature Medicine study,“Optimal dietary patterns for healthy aging (Mar 24, 2025)”—widely discussed for its scale and duration—followed more than 100,000 adults over 30 years to examine how long-term dietary patterns relate to healthy aging.

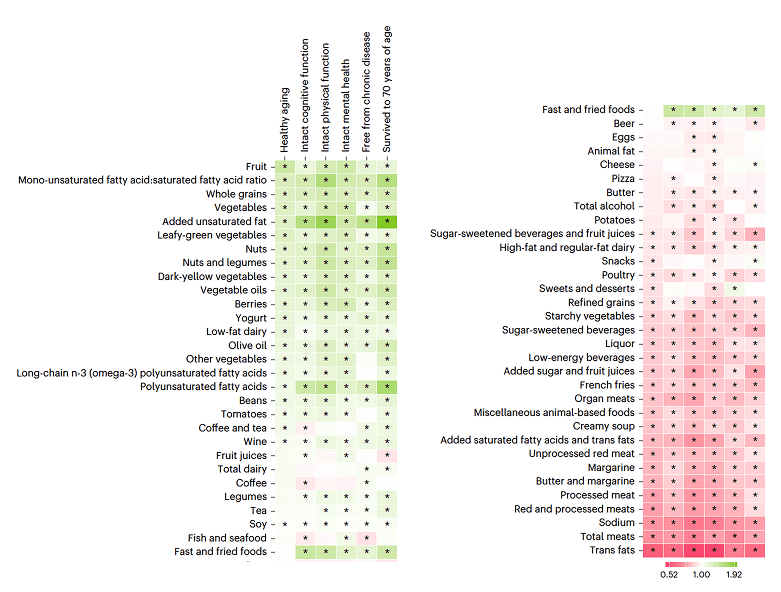

Based on questionnaire data, the researchers assessed the association between adherence to eight dietary patterns*(including intake of ultraprocessed foods) and evaluatedhealthy aging based on survival to age 70 (and 75 in secondary analysis) with no major chronic diseases and intact mental, physical, and cognitive function.

Among the 100,000+ participants, only 9.3% (9,771 individuals) achieved what the study defined as healthy aging. The strongest association was found among those with the highest adherence to the AHEI. Other notable dietary patterns with positive associations included PHDI, DASH, aMED, and rEDIH.

Diets high in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, unsaturated fats, and low-fat dairy were positively associated with healthy aging, while those high in trans fats, sodium, sugary beverages, and processed meats were detrimental.

Notably, ultraprocessed food (UPF) consumption was negatively associated with healthy aging overall.

Interestingly, beer received a higher health score than eggs and red meats, while fast and fried foods also showed a surprising positive association with survival to age 70. These results raise questions about how ‘healthy’ is defined in such scoring systems, and whether cultural norms or residual confounding may influence the outcomes.

* Eight dietary patterns:

AHEI: Evaluates food choices predictive of chronic disease risk.

aMED: Mediterranean diet score.

DASH: Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension.

MIND: A hybrid diet targeting cognitive health.

hPDI: Healthful plant-based diet index.

PHDI: Planetary Health Diet Index — integrates sustainability.

rEDIP: Reversed scores for inflammation and hyperinsulinemia.

UPF: Ultra-processed foods.

The Limits of Scale: Why Big Studies Don’t Always Reflect Truths

Even large-scale, long-term studies have meaningful limitations.

This research depended on self-reported dietary data rather than objective biometrics, introducing the potential for recall bias. The study population lacked demographic diversity—consisting mainly of white, well-educated health professionals—which limits how broadly the results can be applied. It also did not account for genetic differences or common food sensitivities. Additionally, its dietary scoring system was based on Western ideals that may not align with nutritional needs across different populations.

In short, large datasets may uncover general patterns, but they often overlook individual realities.

What Happens After You Eat: Rethinking One-Size-Fits-All Advice

A 2020 study published in Nature Medicine took the conversation deeper—into your bloodstream. The PREDICT 1 study shifted focus to individuals—tracking post-meal responses in 1,000+ healthy adults using blood markers, microbiome data, and genetics.

The results revealed substantial variability in post-meal responses—even when participants consumed identical meals. In studies involving twins, genetics was found to play a moderate role in glucose regulation, but lifestyle and environmental factors dominated responses related to insulin and triglycerides.

Modifiable factors such as meal timing, sleep, physical activity, gut microbiome composition, and recent meal history had stronger influence on postprandial metabolism than genetics. These findings underscore the limitations of uniform dietary advice.

Zeevi et al. also reported a now-famous example where one participant had an exaggerated glycemic response to a banana but not to a cookie, while another showed the reverse.

Personalized predictions are not only feasible—they’re already moderately accurate using current tools.

This research contrasts sharply with large-scale population studies, and highlights why one-size-fits-all nutrition guidance may be increasingly outdated.

From Headlines to the Kitchen: Real-Life Food Contradictions

Let’s return from the studies and zoom into everyday life.

For many of us, nutrition isn’t just theory—it’s what we eat every day, what we grew up believing, and what our body tries to tell us after each meal.

Here are just a few examples that reveal how “common sense” around food doesn’t always hold up:

🥩 Pork fat has long been vilified for its saturated fat content. However, more recent research increasingly points to added sugars and refined carbohydrates—rather than saturated fat alone—as primary contributors to cardiovascular disease risk. Interestingly, a global nutrient-density model still ranked pork fat #8 overall for its content of bioavailable vitamins and healthy fats.

🥛 Milk, nearly mandated in Korean school breakfast programs for decades, was widely promoted as essential for child growth—rooted in Western dietary ideals of calcium and protein intake. However, this population-wide policy overlooked genetic realities: it turns out 75–90% of Koreans are genetically lactose intolerant.

🥦 Broccoli enjoys a superfood status, but it can trigger digestive issues such as bloating, gas, or even thyroid dysfunction in individuals sensitive to goitrogens or FODMAPs. If you frequently feel discomfort after eating broccoli or similar vegetables, try observing how your body reacts—you may find a personalized adjustment makes a meaningful difference.

🍚 White rice, a staple across Asia, may cause significant glycemic spikes in certain individuals—especially when eaten in isolation without fiber or fat. On the other hand, some people may find that high-fiber grains like brown rice or multigrain mixes cause digestive discomfort, such as bloating or gas. Your body’s response to grains varies—observe your reactions over time to discover what grain mix works best for your digestion and energy.

Even “superfoods” can cause harm—if they’re not right for your biology.

From Guidelines to Intelligence: A Feedback-Driven Future

The future of nutrition isn’t about rules—it’s about response.

Listen to your body. Track how you feel.

Use feedback from wearables, blood tests, and symptoms like bloating or drowsiness to adjust your diet with precision.

Traditional research approaches have long followed the DBTL (Design-Build-Test-Learn) model, where experts first set a hypothesis based on their experience and then design studies to test it. While this top-down framework has been the norm for over a century, we are now at a turning point.

This shift mirrors what we’ve seen in the evolution of software algorithms. For decades, human-designed linear models were limited by the assumptions and structures imposed by their creators. But with the rise of deep learning, AI systems have begun to outperform expert-crafted models by learning patterns directly from data in an end-to-end fashion.

I anticipated this shift early. We are methodically building toward a new research paradigm, one that fits into a broader platform roadmap—where insights don’t begin with expert assumptions, but emerge from distributed, diverse, real-world data and adaptive learning.

Leave a comment