RCTs, blockbuster drugs, and outdated trials still shape your care—despite living decades longer and facing a completely different set of diseases.

You’ve Outlived the System Built for Dirty Water and Short Lives—But It’s Still Running Your Health

For 20 years, I’ve worked as a problem solver and system architect—constantly challenging outdated systems and asking fundamental questions when the methods no longer fit the challenge.

When tools don’t match the problem, the cost isn’t just inefficiency—it’s misdirection on a massive scale.

That’s the situation we face in healthcare today.

For over a century, Western medicine has relied on a hierarchy of evidence to guide decisions, with randomized controlled trials (RCTs) being the current gold standard.

RCTs aim to identify treatments that statistically benefit the average person. But this approach was born out of a very different time in 1948 —when medicine focused primarily on managing infectious diseases and public health crises, and when global life expectancy hovered around 30–45 years.

In other words, our gold-standard methodologies were designed in an era that never even faced today’s dominant health challenges. Yet we continue to rely on them without updating the framework for a world where many live into their 80s or 90s—and often spend decades managing system-level dysfunctions, not just acute events.

The Myth of the Average: Who Really Benefits from Clinical Trials?

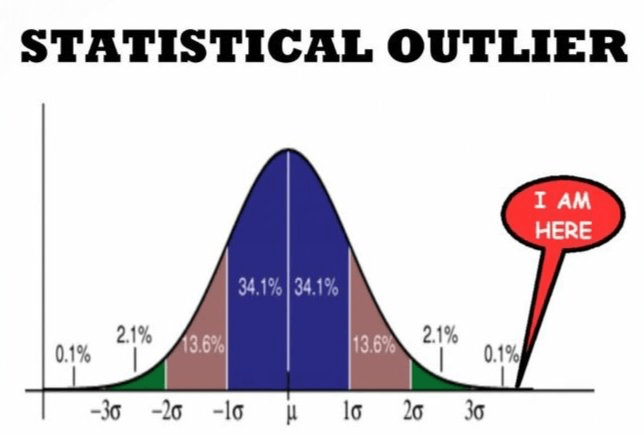

RCTs are designed to eliminate variability—excluding people with overlapping conditions, outlier genetics, or unique lifestyles. This creates clean data, but at the cost of relevance.

Think of it like this: imagine testing whether a new shoe helps people run faster. In an RCT, you would randomly assign people to wear either the new shoe or a standard one, and then compare the average speed increase between the two groups. If the average improves, the shoe is considered effective. But what if it only helps people with flat feet? Or only hurts those with high arches?

The average hides these nuances. Sometimes, an RCT concludes that a treatment works for the average—but many individuals aren’t average. Other times, it concludes the treatment doesn’t work overall, even though it may actually help half the people within that ‘average’ group. These statistical blind spots become dangerous when they inform population-wide policies or guidelines.

They work well for point-specific diseases in large public populations—like antibiotics for bacterial infections or vaccines for viral outbreaks. But the chronic and metabolic diseases we now face, the ones killing millions worldwide, are a different kind of problem. They’re not isolated malfunctions, but systemic failures.

Worse, they’ve historically excluded key populations: women (especially pre-2000), older adults, ethnic minorities, and people with multiple conditions.

I know this firsthand. For over a decade in childhood, I struggled with medications that didn’t work—and brought side effects instead. That frustration made me question the very idea of ‘average-based’ care.

Today’s chronic diseases are system-level failures. Treating them with one-variable trials is like fixing one cog in a failing engine. The average person doesn’t exist. And without context, data misleads.

It’s time we shift from statistical generalizations to personalized precision.

The Business Model That Kept the System Running: How Economics and Methodology Reinforced Each Other

Traditional drug development evolved alongside RCTs—built to find one molecule that works for the most people, in the most predictable way. But the process has long relied on trial-and-error: synthesize hundreds of compounds, test them in animals or cells, and hope a few work in humans. It’s a blunt, high-cost pipeline designed to produce ‘blockbuster drugs’ that treat broad populations.

That model made sense in the age of acute disease and top-down regulation—but it was never built to handle subtlety, individual variability, or long-term prevention. In fact, it had little incentive to focus on prevention at all—because prevention doesn’t fit easily into short-term trials or high-return drug pipelines.

AI now accelerates this loop—screening molecules faster, prioritizing candidates—but hasn’t yet redefined the process. It still operates on legacy assumptions: that success means finding something that works for a statistically significant group.

Precision medicine aims to flip this model—from one-size-fits-all to right-drug-for-the-right-person. Instead of treating disease as a static condition, we begin treating it as a dynamic, individualized state—shaped by environment, lifestyle, genetics, and even time of day.

Aging Isn’t a Malfunction—It’s a Map of Interconnected Decline

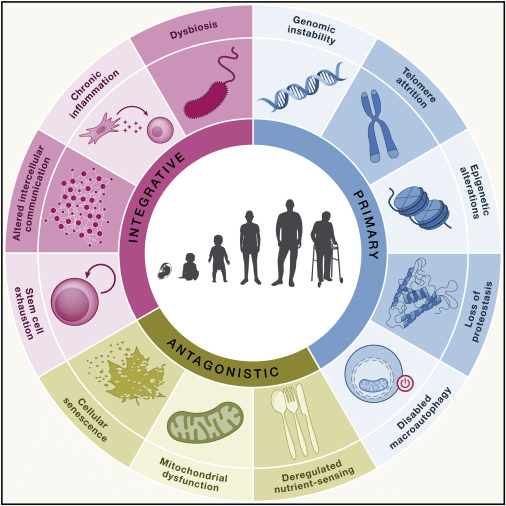

Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe

Chronic and metabolic diseases aren’t caused by a single ‘bad actor’; they’re symptoms of systemic failure. We’re now tasked with solving a fundamentally different kind of problem—systemic, dynamic, and individualized.

As these system-failure diseases grew more prevalent, researchers began to realize that addressing aging itself—rather than chasing symptoms—could offer a more upstream, unified approach.

Starting in the early 2000s, we saw a surge in aging-related research, from cellular senescence and mitochondrial dysfunction to epigenetic drift and inflammaging. These studies didn’t just aim to extend life, but to preserve function and delay the onset of multi-system decline.

In other words, aging became the master key—a common denominator behind many modern chronic conditions.

Understanding and modulating aging processes is no longer just about living longer; it’s about living better, with fewer breakdowns along the way.

Leave a comment